Before we jump into a complex topic like copyright termination…Quick!

Off the top of your head…name 3 songs from the early 1990s that spark a good memory for you.

(leave a comment at the bottom of this post…I’m curious to see the musical taste of people who read this article).

For me there were a ton of songs and groups in the early 1990s that were inspiring but here are the ones that immediately came to mind (I had an eclectic upbringing).

My list would be:

– Come and Talk To Me – Jodeci

– Warm it Up – Kris Kross

– La Schmoove – Fu-Schnickens

How does this tie into the Copyright Termination Rights? Well, the artists and/or writers of these songs may have the legal right to regain ownership of their copyrights if they fit certain criteria (I have not analyzed these particular situations listed above).

The topic of Copyright Termination Rights is by far the best kept secret in the entertainment industry.

About 13 years ago I wrote a few blogs, and did this video, on this topic.

Since then I have been heavily involved in this area of law. I have sent Notices of Termination to the major publishing companies on behalf of songwriters and producers, and I have helped my publishing company clients negotiate settlements when they have received Notices of Termination from their songwriters and producers.

But what is the state of this so-called “termination right” that was supposed to level the playing fields by giving artists and writers the power to take back their rights, or at least give them some leverage to re-negotiate lopsided deals that they made 35-40 years ago (or, in the case of some pre-1978 compositions, the window can be 56-61 years ago)

Well, let’s start with a recap of what I am talking about so that everyone is on the same page, and then I’ll talk about what’s been going on recently.

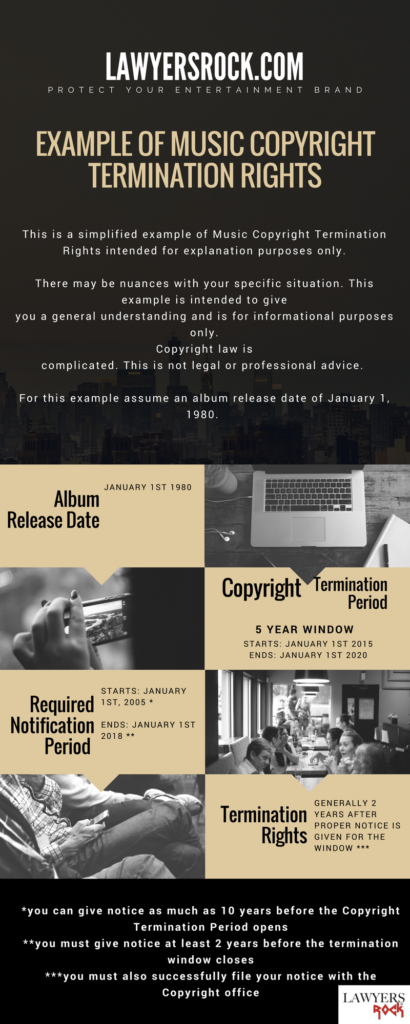

First let me give you a quick example of copyright termination rights with an Infographic. This will give you a quick break down of what a timeline would look like.

Below the Infographic I have a detailed article on what copyright termination rights are and how they work.

__________________________________________________________________________

Infographic: Example of Copyright Termination Rights

Want to share this image on your site? Just copy and paste the embed code below:

What Is The Copyright Termination Right?

The Copyright Termination Right sounds like a bunch of legal jargon, but what if I told you that it was possible for you, songwriter or music producer, to take back ownership of your music from the publishing or other media company that “encouraged” you to take an undesirable deal years ago.

Most writers wonder how this is possible when they signed agreements that clearly transferred all of their rights in the compositions to the publisher.

The short answer is that the U.S. Copyright Act includes two statutory termination provisions known as Section 203 (post-1978) and Section 304(c) (pre-1978) “copyright termination rights,” that actually supersede any contract that was signed by an author songwriter or producer. If certain criteria are met, the author or the author’s estate can recapture ownership of his or her copyright in the songs.

What about a termination right for recording artists in sound recordings? Unfortunately, in recent years, courts have denied that such a right exists; however, the fight to reverse this precedent continues.

What Is The Basis For This Law?

Particularly, there are two main reasons why a creative person may possess this right:

First, in the early 20th Century, the U.S. Congress initially created law to protect young authors from having to settle for bad deals that were made for the life of the copyright because at the time, struggling authors had no leverage to negotiate his or her original contracts.

More recently, Congress, through the 1976 Copyright Act (which actually didn’t take effect until January 1, 1978) reiterated this concept by ensuring that an author would have a chance to re-evaluate the value of a copyright after 35 years (or after 56 years for pre-1978 works), and either re-negotiate a deal with the original contracting party, who would likely be open to more fair negotiations, or go elsewhere and make a new deal with another party for the remainder of the copyright life.

Second, federal law, such as the Copyright Act, takes precedence over any state laws, including contract law, so if a direct conflict exists between the two then the federal law governs. This means that an author’s Copyright Termination Right cannot be waived, sold in advance, or otherwise forfeited by contract.

In short, taking advantage of a songwriter or composer is not only unconscionable, but literally unconstitutional.

Even though an author signs a contract that says something like, “all rights are assigned and transferred for the life of the copyright”, which is common language in publishing deals, such a provision is void and ineffective when it comes to an author’s right to terminate the contract assignment and regain control of his or her work pursuant to the Copyright Act.

What Is The Effect of Termination?

Upon the effective date of termination, all of the author’s previously transferred or licensed copyright rights covered by the terminated grant revert to the author or proper person(s) if the author is deceased.

Exercising the termination right does not extend or otherwise modify the original copyright term.

A copyright for an individual author under the 1976 Copyright Act lasts for the life of the author plus 70 additional years. If, on the other hand, the work is a work of corporate authorship, the copyright duration is 95 years from the date of publication or 120 years from creation, whichever expires first.

A proper termination of the rights to one can be transferred again for the remainder of the life of the copyright.

When Can The Right Be Terminate?

For rights granted in works created after January 1, 1978, a songwriter/composer has the right to terminate the granted rights during a five-year period beginning 35 years after the agreement was signed. The legal term for this date is the “execution date of the grant.” This five-year period may be altered to begin on the release date of the music if the agreement also granted the publisher the right to publish music, which most agreements did. The songwriter/composer must send the publisher a proper Notice of Termination, which can be sent as early as 10 years before the 35-year period begins and as late as 2 years before the 40-year period ends.

For example, if music was released on January 15, 2000, a notice of termination can be served as early as January 15, 2025 (effective January 15, 2035), but no later than January 15, 2038 (effective January 15, 2040). You’ll probably need a calculator and a few examples to get the hang of this calculation. Luckily, the U.S. Copyright Office website has created official handy tables to help calculate the date.

For rights granted in works secured prior to January 1, 1978, the start date, time period, and calculation are different. Unfortunately, this term is not clearly defined in the Copyright Act. Many scholars have interpreted it to mean the copyright registration date.

The 5-year termination window begins 56 years following the date that copyright rights are “secured”. The window to give notice is the same.

For example, if music was released on January 15, 1970, a Notice of Termination can be served as early as January 15, 2016 (effective January 15, 2026), but no later than January 15, 2029 (effective January 15, 2031). The Copyright Office website also has a table for this calculation.

Who Can Challenge An Author’s Termination Notice?

The original author or the author’s heirs clearly have the right to termination copyrights; however, more complicated situations may not be as clear. One such case already decided on the basis of standing involved a termination claim brought by the children of Ray Charles against the Ray Charles Foundation. Though the foundation had become the legal owner of the rights in Charles’ songs, the grant of rights was originally given to Atlantic Records, and later renegotiated to its’ successor-in-interest.

Since only the original grantee can challenge the termination claim, the court determined the foundation had no standing to challenge the claim because they were merely the “beneficial owner” of the copyright interest, rather than the party who was originally granted the transfer.

How Exactly Does This Right Work?

To qualify for the Copyright Termination Right, the transfer or license must have been executed by the author, not by a recipient of an author’s rights (i.e., heirs by will). However, statutory heirs of the author(s) may still able to affect the termination rights if the author who executed the transfer is since deceased.

I won’t go into the details (that would turn this into a book) but if the original author transferred or licensed the rights, then the discussion of the following issues will give authors some guidance as to whether the rights in their work may be eligible for revision:

When Did The Author Transfer or License The Rights?

The first fact to determine is when the grant of rights in question was executed. A longer analysis applies to works that were created prior to January 1, 1978 because Copyright Law prior to this date was more complex.

Within this sub-topic you have to analyze whether the work is considered a pre-1978 work, a post-1978 work, or a so-called “gap” work where may have been contracted or written before 1978 but actually created or released after 1978.

Was The Copyright Created As A “Work-Made-For-Hire”?

A work-made-for-hire is a work prepared by an employee within the scope of his or her employment for the employer so copyright termination does not apply.

It is also a commissioned work, falling under one of the specially designated categories of such works, where the parties agreed in writing to treat it as a work-made-for-hire (“WFH”).

Certain works are clearly defined in the WFH definition, but there are also several types of work that are excluded entirely, particularly music.

This creates some ambiguity and when the work is not mentioned, a deeper analysis may be required, or possibly a lawsuit to clarify.

Upcoming lawsuits will feature arguments from both sides concerning whether sound recordings can qualify as a WFH. Labels will take the position that albums fall under a qualifying category such as a “collective work” or “compilation.”

Most music agreements contain both WFH language and assignment language as an attempt to hedge bets on what a court will say one day.

Also, many agreements with WFH language also contain clear language that the artist is not an employee of the record label. By the way, did you know that California’s labor code states that any agreement with work-made-for-hire language in it automatically means that the contracting party is a statutory employee?

I’ll save that topic for another blog.

Who Can Terminate The Copyright?

Generally, if the author is still alive then this answer is easy, the author can terminate the copyright. If the author is not alive then it can get complicated, but the short answer is the author’s heirs have the right to terminate assignments, (again, provided the deceased author made the assignment).

Are There Any Exceptions?

It is worth noting that the Copyright Termination Right does not apply to derivative work prepared under authority of the grant before termination of the grant. A derivative work is a creation that is based on an original work, such as an updated version of original music.

The derivative user may continue to use that work, but no new derivative works can be created after termination.

This topic will be a hot button for many years to come. There are currently a number of active cases that will shape the future of this right so stay tuned!

And if you happen to run into Teddy Riley, Sarah McLachlan, Carole King or another prolific songwriter or producer, please share this article with them!

Until next time!

Updated and reposted: September 19, 2023